They say I live a fast life.

Maybe I just like a fast life. I wouldn't give it up for anything

in the world. It won't last forever, either. But the memories

will ... Dennis Wilson

When he spoke those words in

1965 maybe Dennis Wilson really believed that the fast life couldn't

last forever, that someday he'd grow up. He was 20 then, and

he had plenty of time. But Dennis, the only real surfer in the

Beach Boys supergroup, never stopped living the adolescent fantasy

he helped immortalize in classic hits like Surfin USA, Little

Deuce Coupe and Help Me Rhonda fast cars, easy chicks, perfect

waves and endless summers. When his lifeless body was pulled

from 13 feet of murky water off a Marina del Rey boat slip late

last month, the innocence of those pleasures was long lost. At

39, Wilson had drowned after a day of drinking and diving into

bone-chilling 58-degree water clad only in cutoff jeans and a

face mask.

As friends and family mourned

Wilson's death, they drew a portrait of a vastly untidy life,

one forgivable in a teenager, pitiable in a middle-aged man.

Athletic, wild and charming, he had the surfer's indifference

to possessions, squandering millions on good times and friends.

Rootless, at the end he had no home, crashing each night at a

friend's place or a cheap hotel. A compulsive womanizer, he had

had five marriages, a new woman always on his arm and a recent

union that shocked some. Last summer he wed Shawn Love, now 19,

the daughter of his first cousin and fellow Beach Boy Mike Love,

and the mother of his fourth child, a son, Gage, born the previous

year. Also a big partyer, he had brushes with drugs over the

years-and a long spiral into chronic alcoholism.

The drinking had become so bad,

in fact, that the Beach Boys-Love, Dennis' brothers, Carl and

Brian Wilson, and friend Al Jardine-had barred him from several

concerts. Through the years the Beach Boys had been one of rock's

most troubled groups, with publicized drug hassles, internal

feuds and Brian's psychiatric problems. But recently the band

gave Dennis a warning: If he didn't dry out, he could not join

the group's upcoming tour.

A few days before Christmas he

checked into the detox unit at St. John's Hospital and Health

Center in Santa Monica. Dr. Joe Takamine, who runs the 21-day

detox program, said a blood test taken on admittance showed a.28

alcohol level and traces of cocaine. "He told me he was

drinking about a fifth of vodka a day and doing a little coke,"

Dr. Takamine adds. "I put him on 100 mg. of Librium every

two hours so he could come down slowly and maybe start the program

in five days." On Christmas, however, he suddenly left.

He spent that day drinking with a friend. At 3:30 a.m. Dec. 26,

he reportedly checked into the Daniel Freeman Marina Hospital

but walked out the next day and later met with Shawn. Then he

took off again.

His last night alive was spent

aboard the 52-foot yawl Emerald, owned by his friend Bill Oster.

Dennis was with a friend named Colleen McGovern. The marina once

had been home-before he was forced to sell his beloved 62footer,

Harmony, in 1980 to satisfy back bills and bank loans. He reportedly

awoke by 9 a.m. and began hitting on vodka. "We went rowing

in the morning, got some cigarettes, had lunch on the boat-turkey

sandwiches," remembers Oster. "Dennis was in a good

mood, happy. We were plotting how to buy his boat back."

(Wilson's business manager, Robert Levine, had offered to repurchase

the boat for him if he went 30 days without drinking.)

By noon a yacht manager, Skip

Lahti, 26, who had known Wilson for a couple of years, says,

"He was staggering around pretty good." Wilson napped

for an hour or so, awoke, then visited Lathiel Morris, a retired

friend living in a houseboat near the Emerald's slip. He seemed

excited rather than drunk to Morris. "He said, 'I'm getting

my boat back,' " Morris recalls. Wilson eyed Morris' 16-year-old

granddaughter. Then he complained about his impending divorce.

"How many does that make?" Morris asked. "The

sixth, I think," Wilson answered. "I'm lonesome. I'm

lonesome all the time." Morris adds, "I saw he was

with this beautiful brunette [Colleen] and said, 'Ahhh, baloney.'

He said, 'We've only been going out a couple of weeks.' "

Morris next saw Wilson around

3 p.m. He had begun diving into the water next to the Emerald's

slip, retrieving from the soft bay floor sea-corroded junk that

he had thrown off the Harmony when it was anchored there: a rope,

some chains, a steel box and, eerily, a silver frame that once

held a photo of an ex-wife, model/actress Karen Lamm. "He

was in and out of the water, getting a kick out of all the stuff

he was finding," recalls Lahti. After diving for about 20

minutes he came out of the water shivering badly, warmed up and

ate another sandwich. About 4 p.m. he went back in. "He

thought he found a box. He called it a chestful of gold,"

says Oster. "It was probably a toolbox. He was just being

Dennis, entertaining everybody, being his lovable self, goofing

around."

About 4:15 p.m. he came up for

the last time. "He didn't indicate any problem," says

Oster. "I saw him at one end of the slip. He blew a few

bubbles and swam to the dinghy very quietly. It was like he was

trying to hide. I thought he was clowning. I jumped on the dock

to flush him out and then we would all laugh." When Wilson

couldn't be found, Oster flagged a passing harbor patrol boat.

Meanwhile, Oster, Morris and Lahti frantically searched the deserted

docks and nearby bars for Wilson. Lahti, who knew Dennis to be

a practical joker, volunteered to dive in, but Oster thought

it was a typical "crazy-Dennis" stunt. "I told

Bill we'd have surely found him after 20 minutes," Lahti

recalls. "Bill said, 'No, he's still joking. He's known

to do this sort of thing.' As divers plunged in and probed the

bay in the dark, Oster still hoped that Dennis would surface

somewhere.

It was about 5:30 when they found

Wilson. Four divers had been searching for him and had rigged

a long pole to probe the bottom. That was where they found him,

directly below the empty slip. Coroner reports called it an accidental

drowning" but a fuller toxicological report will be made.

"He did drink a lot and had a lot of wild parties,"

says a shaken Morris, 57. "But he was one swell guy, thoughtful,

considerate, even when drinking. I just can't figure out why

they let him dive down there. I know it's hindsight now, but

he lost his life for nothing."

Dennis' death brought together

though briefly and acrimoniously long-split factions in the Beach

Boys' extended family. At a 30-minute funeral service at an Inglewood,

Calif. cemetery chapel three days after the drowning were his

mother, Audree, the band members and close associates. And the

women and children: Shawn, with whom Dennis had lived for almost

three years; first wife Carol Freedman, 37, her son, Scott, 21,

from a prior marriage, and her 16-year-old daughter, Jennifer,

Dennis' oldest child; second wife Barbara Charren, 38, and their

sons, Carl and Michael, 12 and 11; and Karen Lamm, who was married

twice to Dennis during the late '70s.

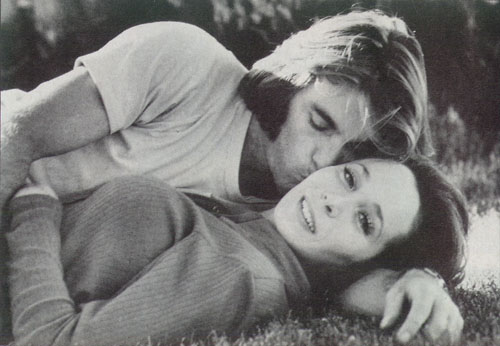

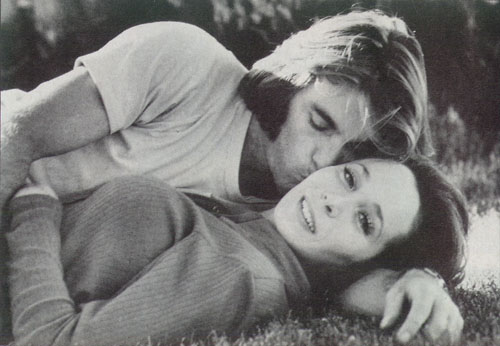

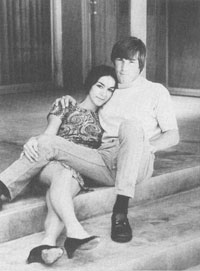

Dennis was like a second father to first

wife Carol's son, Scott, and they had a

daughter, Jennifer, together.

By several accounts, the family

was bitterly divided over the funeral and plans to bury Dennis

at sea. The clan reportedly split into two factions, those allied

with the Wilson family and those who fell into the Shawn Love

Wilson camp, reflecting long-simmering rivalries within the Beach

Boys themselves. At a family funeral conference, ex-wife Lamm

reports, "I suggested playing Farewell My Friend [Dennis'

1977 song]. I also said I wanted to read a passage from Corinthians

about unconditional love, which is what Dennis was all about.

Shawn said, 'You can't read it.' She's not the nicest girl."

Shawn and Jennifer wound up reading the text, and, with the backing

of her mother, Shannon Jones, Shawn also had her way about the

burial. Reportedly, when Dennis' brother Carl flew in from Colorado,

he made plans to have Dennis buried in Inglewood Cemetery next

to their father, Murray, who died in 1973. Shawn vetoed that

plan, claiming that Dennis had told her he wanted to be buried

at sea. Since the coroner would release the body only to Dennis'

wife, the family had no choice but to accede to Shawn's demand.

Dennis' children are plainly

suffering. Shawn reports 16-month-old Gage keeps looking around

for his dad, who played hide-and-seek with him. Exwife Barbara

says Michael (whose 11 th birthday fell on the day of his father's

service) told her, "Mommy, things will never be the same

again. No one can make me laugh like Daddy can." The boy

was also upset that "they're dumping Daddy's body over a

boat that's disgusting." Carl complained that he had someday

"wanted to be buried next to his father."

A loving if often absent dad, Dennis hugged sons Michael and

Carl

at third son Gage's first birthday party last fall.

The family turmoil was nothing

new. Dennis Wilson-born midway between Brian, now 41, and Carl,

37-grew up amid violence at home in Hawthorne, Calif., five miles

from the Pacific. His father, Murray, a frustrated songwriter

who had lost an eye while employed at a rubber plant, was a "tyrant,"

Dennis once said. "I don't know kids who got it like we

did." He burned Dennis' hands after he played with matches.

Brian's deafness in one ear may have been the result of a beating.

"He beat the crap out of me," Dennis once recalled.

"The punishments were outrageous." Small wonder that

Dennis, having discovered the exhilarating freedom of the surfboard

at 13, would help inspire the band's vision of rebellion and

freedom in the teen beach culture.

Brian, the group's most gifted

musician and composer, turned their simple rock structures into

elaborately tiered studio art, surpassed only by that of Lennon

and McCartney in the late'60s.

But by the time that happened

they were surrounded by L.A.'s drug world. They made albums heavily

influenced by Brian's experimentation with LSD. They flirted

with the then-fashionable TM. In one notorious episode, Dennis

befriended the demonic madman Charles Manson, whose "family"

moved into his palatial Beverly Hills mansion for several months,

sponging some $100,000 off him and wrecking an uninsured $21,000

Mercedes. Manson and Wilson apparently collaborated on one song

(Never Learn Not to Love, on the Boys' 20/20 LP), but Dennis

wised up and got the maniac out of his life some time before

the grisly 1969 Tate-LaBianca murders. That experience left his

self-confidence shaken for years.

As the Beach Boys' music went

into eclipse in the late'60s, Dennis seemed increasingly to turn

his energy against himself. There were the failed marriages;

a disappointing film debut, Two-Lane Blacktop in 1971; sloppy

performances during the band's road revival in the mid-'70s and

a cranky detachment from touring. A solo LP (Pacific Ocean Blue

in 1977) earned favorable reviews but didn't really sell.

And his relationships with women

didn't jell. His tempestuous marriages to Lamm became mired in

cocaine and booze. "Drinking broke us up," says Karen.

"it hurts to see someone you love go down." Karen has

been a member of Cocaine Anonymous and Alcoholics Anonymous for

almost two "clean" years, but Dennis couldn't resist

the drugs. After they broke up in 1978 Dennis took up with Christine

McVie of Fleetwood Mac, but that affair ended after two years.

"Dennis was just so empty inside," says ex-wife Barbara.

"He never realized what a unique person he was. He tried

to fill that need any way he could. When we were living together,

he loved the sense of family. The only problem was that he couldn't

stay long. He always had to leave and come back."

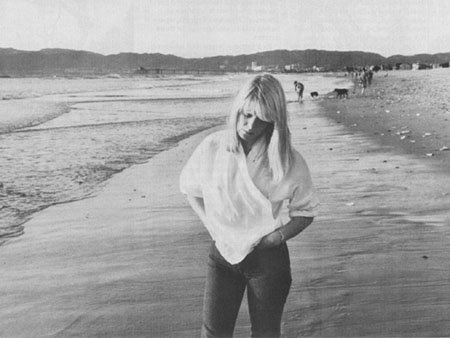

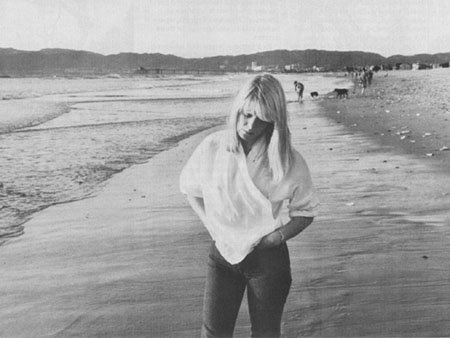

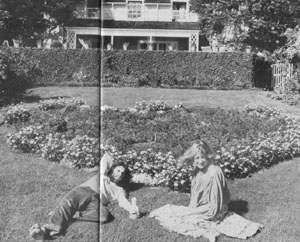

Dennis surprised girlfriend Christine McVie with the

heart-shaped garden at her home in 1979.

There were financial imbalances

as well as emotional ones. Steve Love, Beach Boys manager during

most of the '70's says Dennis' alimony and child support payments,

as well as outrageous "extravagances" -- fancy cars,

diamonds and furs for girlfriends-ate up an income that sometimes

hit $600,000 annually. "It's hard to imagine," says

Love, "that anyone could just blow so much money, but Dennis

did. He was totally unrestrained and undisciplined; he was foolishly,

self-destructively generous."

When all the veneer is stripped

away, the truth about the Beach Boys is that ex-Interior Secretary

James Watt was only partly wrong in last year's famous gaffe

about the group attracting "the wrong element." They

didn't attract it so much as conceal what lurked beneath the

surface of their own innocent myth. The problems of elder brother

Brian Wilson, long a reclusive LSD casualty, have been well documented.

Now some see it as ironic that while the delicate Brian was under

24-hour psychiatric care at a cost rumored to hit $50,000 a month,

Dennis, the group's vigorous and daring roughneck, was unable

to commit himself to treatment. "I would tell him he was

drinking too much and hurting himself," Love says. "But

he rebelled against restraints, whether man-made or natural."

After the funeral service, the

band gathered at co-manager Tom Hulett's house. "We were

sort of having a wake," says Love. A nondrinking vegetarian,

Love nevertheless showed up with four bottles of the most expensive

champagne he could find. "Dennis would have wanted it this

way," he said. Mike and Brian shot some basketball. "I

told Brian I thought the best thing we could do was write a song

for Dennis," Love adds. "We didn't work on it that

night. We just talked and toasted Dennis and the New Year. We

were all so much a part of each other that I'm sure we'll miss

him every single day the rest of our lives. There's no way we'll

not miss him."

People Magazine January 16, 1984

Written by Jim Jerome; reported by Gail Buchalter, Hilary Evans,

Sal Manna, Joseph Pilcher and Salley Rayl.